A story about Helen Keller, a civil rights activist and lecturer despite being blind and deaf, her teacher the partially blind Anne Sullivan Macy (referred to hereafter as Sullivan), and an unnamed maid whose alleged act of kindness changed Sullivan’s and Keller’s lives, has been a topic of conversation for decades. In 2021, the following lengthy parable was shared on social media, along with a photograph supposedly showing Sullivan and Keller:

The story reads:

Dr. Frank Mayfield was touring Tewksbury Institute when, on his way out, he accidentally collided with an elderly floor maid. To cover the awkward moment Dr. Mayfield started asking questions.

“How long have you worked here?”

“I’ve worked here almost since the place opened,” the maid replied.

“What can you tell me about the history of this place?” he asked.

“I don’t think I can tell you anything, but I could show you something.”

With that, she took his hand and led him down to the basement under the oldest section of the building. She pointed to one of what looked like small prison cells, their iron bars rusted with age, and said, “That’s the cage where they used to keep Annie Sullivan.”

“Who’s Annie?” the doctor asked.

Annie was a young girl who was brought in here because she was incorrigible—nobody could do anything with her. She’d bite and scream and throw her food at people. The doctors and nurses couldn’t even examine her or anything. I’d see them trying with her spitting and scratching at them.

“I was only a few years younger than her myself and I used to think, ‘I sure would hate to be locked up in a cage like that.’ I wanted to help her, but I didn’t have any idea what I could do. I mean, if the doctors and nurses couldn’t help her, what could someone like me do?

“I didn’t know what else to do, so I just baked her some brownies one night after work. The next day I brought them in. I walked carefully to her cage and said, ‘Annie, I baked these brownies just for you. I’ll put them right here on the floor and you can come and get them if you want.’

“Then I got out of there just as fast as I could because I was afraid she might throw them at me. But she didn’t. She actually took the brownies and ate them. After that, she was just a little bit nicer to me when I was around. And sometimes I’d talk to her. Once, I even got her laughing.

One of the nurses noticed this and she told the doctor. They asked me if I’d help them with Annie. I said I would if I could. So that’s how it came about that. Every time they wanted to see Annie or examine her, I went into the cage first and explained and calmed her down and held her hand.

This is how they discovered that Annie was almost blind.”

After they’d been working with her for about a year—and it was tough sledding with Annie—the Perkins institute for the Blind opened its doors. They were able to help her and she went on to study and she became a teacher herself.

Annie came back to the Tewksbury Institute to visit, and to see what she could do to help out. At first, the Director didn’t say anything and then he thought about a letter he’d just received. A man had written to him about his daughter. She was absolutely unruly—almost like an animal. She was blind and deaf as well as ‘deranged.’

He was at his wit’s end, but he didn’t want to put her in an asylum. So he wrote the Institute to ask if they knew of anyone who would come to his house and work with his daughter.

And that is how Annie Sullivan became the lifelong companion of Helen Keller.

When Helen Keller received the Nobel Prize, she was asked who had the greatest impact on her life and she said, “Annie Sullivan.”

But Annie said, “No Helen. The woman who had the greatest influence on both our lives was a floor maid at the Tewksbury Institute.”

This is a genuine photograph of Sullivan and Keller, and there is a lot of truth in this story. Sullivan really was partially blind, and she lived the early part of her life at an overcrowded facility in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, where conditions were deplorable. Sullivan was also educated at the Perkins Institute for the Blind, and would later become Helen Keller’s teacher. The portion of this story about an anonymous maid’s act of kindness are unverified, however, and the closing anecdote about Sullivan’s response to Keller’s Nobel Prize statement is factually impossible.

Where Does This Story Come From?

The above-displayed anecdote is a near-verbatim reproduction of an article entitled “People Make the Place” by Leah Curtin, a registered nurse, that was published in the 1993 issue of Nursing Management Magazine. Curtin’s version starts with two introductory paragraphs claiming that she heard this story from Dr. Frank Mayfield, a neurosurgeon who founded the Mayfield Clinic in Ohio, while she was a nursing student. It should be noted that this is not a contemporaneous story, but a third-hand retelling of a story the author (Curtin) reportedly heard “about 100 years ago” from a doctor (Mayfield) who supposedly heard it from an unnamed maid.

While it is certainly possible that Mayfield heard some version of this story from a maid while touring the Tewksbury Almshouse, the quotes in this story are fabricated. And while it’s possible that a maid at the Tewksbury almshouse showed some kindness to a young Sullivan, we have not been able to find any other sources to confirm this anecdote.

Was Sullivan Kept in a Cage?

The early years of Sullivan’s life were difficult, to say the least. She was born in 1866 to two Irish immigrants who came to America during the Great Famine. At the age of 5, she suffered severe vision loss after contracting trachoma. When her mother died a few years later, her father abandoned Sullivan and her siblings at a poorhouse in Tewksbury.

The American Foundation for the Blind described the conditions at the Tewksbury Almshouse, writing:

Tewksbury was infamous throughout the state of Massachusetts. By 1874, the population included alcoholics requiring treatment, as well as those labeled “pauper insane.” The largest group were poor immigrants from Europe. During Anne’s time at Tewksbury, the majority of these were Irish Catholics.

Rumors circulated throughout the state about cruelty to inmates at the institution, sexually perverted practices, and even cannibalism.

Author Nella Braddy provided a detailed account of Sullivan’s stay at Tewksbury (one that relied in part from Sullivan’s own memory) in her 1933 book “Anne Sullivan Macy: The Story Behind Helen Keller.” Braddy writes that Sullivan and her brother spent their first night at the poorhouse in a “cell” that was primarily used as the “dead house”:

The two children spent the first night in a small dark enclosure at one end of the ward. There was one bed in it, a table, and an altar. This enclosure, though they did not know it and would not have been troubled if they had, was the “dead house” into which corpses were wheeled to wait for burial.

They slept together, unhaunted by the shades of the old women who had spent their last moments above the sod lying, just as they were lying, with their faces to the ceiling. But perhaps the ghosts were not there. With the wide world to choose from it is not likely that any of them had lingered in this sad, drab, dreary little cell.

After they were processed the following morning, Sullivan and her brother were moved to the women’s ward (a compromise to let the two children stay together) where they had a “cot apiece.” Braddy continues:

They had a cot apiece in the ward, and they had the dead house to play in …

The children were, on the whole, left to themselves. Most of the women were too near dead to care for anything. Most of them wanted to die and most of them did not have to wait long. Death was the most casual and the most common of occurrences. Nobody cared when it came …

Even the death of one of their number brought little comment, if any, from her neighbours. It evoked no fluttering of nurses, no calling the doctor, no fuss at all except what the patient made—the death rattle, a cry, or a groan, and often not even so much as this. The one friend still left to all of them was death. In a little while the cot would be wheeled into the dead house, the metal wheels clattering ominously over the wooden floor. The sound of the wheels was not so horrible to Annie during her first days at the almshouse, for she gave it no special meaning, but it made an indelible impression, and to-day, after she has been away from it more than fifty years, she can still sometimes at night hear its hollow and remorseless echo.

Did a Maid Bring Sullivan Brownies?

The viral text claims that an anonymous maid brought brownies to Sullivan during her stay at Tewksbury in an attempt to win over an unruly child. While we can’t confirm this portion of the story (this anecdote comes from a nurse who heard it from a doctor who reportedly heard it from a maid decades earlier), and while it’s worth noting that descriptions of Sullivan as a child do not present her as particularly aggressive or wild, we can say that some staff members and residents at Tewksbury truly did show Sullivan kindness.

Braddy notes that Maggie Hogan, a “quiet little woman with a crooked back” who oversaw the ward, introduced Sullivan to the small administrative library, and worked to get other residents to read books to her. Braddy writes:

These three wards were under the care of a sad, quiet little woman with a crooked back, Maggie Hogan, who moved about among them like a grey angel, soothing them when they wept, calming them with soft sweet words when they cowered before the pain of bringing new life into the world. The girls called her “Little Mother,” and she was godmother to all their children. Those that seemed likely to die before the priest came she baptized herself, going through all the details of the familiar ceremony, even lighting the candles …

It was Maggie Hogan who introduced her to the small library in the administration building, and it was Maggie who selected her first books, taking only those whose authors were unmistakably Irish. And it was Maggie who persuaded a mildly crazy girl by the name of Tilly Delaney to read them to her. Later Annie selected the books herself. Her system was to choose from the titles (she could not see them) which the superintendent read out to her: Cast Up by the Sea, Ten Nights in a Barroom, Stepping Heavenward, The Octoroon, The Lamplighter, Darkness and Daylight, Tempest and Sunshine.

Sullivan’s thoughts about Tewksbury were recorded in Braddy’s book, as well as in a manuscript she wrote entitled “Foolish Remarks of a Foolish Woman.” While Sullivan acknowledged that there had been some “unexpected good” during the “chinks of frustration in my life,” we didn’t find any record of Sullivan claiming that her life had been changed by a random act of kindness. Rather, she wrote in her manuscript that she was still haunted by her time at Tewksbury.

Unexpected good has filled the chinks of frustration in my life. But at times melancholy without reason grips me as in a vice [sic]. A word, an odd inflection, the way somebody crosses the street, brings all the past before me with such amazing clearness and completeness, my heart stops beating for a moment. Then everything around me seems as it was so many years ago. Even the ugly frame-buildings are revived. Again I see the unsightly folk who hobbled, cursed, fed and snored like animals. I shiver recalling how I looked upon scenes of vile exposure—the open heart of a derelict is not a pleasant thing. I doubt if life, or eternity for that matter, is long enough to erase the errors and ugly blots scored upon my brain by those dismal years.

How Did Sullivan Meet Keller?

The conditions at Tewskbury were so bad that Samuel Gridley Howe, a founder of the Perkins School for the Blind, launched an investigation into the school. As officials toured the facility, Sullivan approached them and begged to attend their school for the blind.

Perkins describes this moment on their website, writing:

In 1880, Anne Sullivan learned that a commission was coming to investigate the conditions at Tewksbury Almshouse. On the day of their visit, Sullivan followed them around, waiting for an opportunity to speak. Just as the tour was concluding, she gathered up all of her courage, approached a member of the team of inspectors, and told him that she wanted to go to school. That moment changed her life. On October 7, 1880, Sullivan entered the Perkins Institution.

Sullivan’s life experience made her very different from the other students at Perkins. At the age of 14, she couldn’t read or even write her name. She had never owned a nightgown or hairbrush, and did not know how to thread a needle. While Sullivan had never attended school, she was wise in the ways of the world, having learned a great deal about life, politics and tragedy at Tewksbury, a side of society unknown even to her teachers.

In the viral version of the story, Sullivan returns to Tewksbury to visit, and is told by the director that he had just received a letter from a parent asking for a teacher for their “deranged” daughter, Helen Keller. This, however, does not quite line up with the historical record.

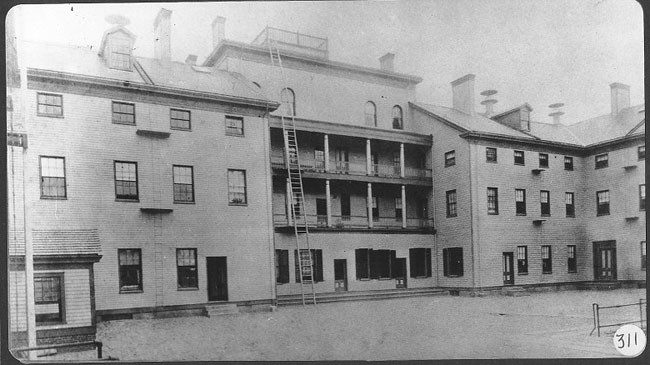

Here’s a photograph of Keller and Sullivan from 1888:

In 1886, at the recommendation of Alexander Graham Bell (yes, the inventor of the telephone) Keller’s parents sent a letter to Michael Anagnos, the director of Perkins, seeking a teacher for their daughter. Anagnos immediately thought of Sullivan for the position and sent her a letter. Sullivan was not only a gifted student who overcame severe difficulties to graduate as the valedictorian of her class, but she also had experience working with deaf-blind people, as she had befriended Laura Bridgman, regarded as the first deaf-blind American to receive a significant education, during her time at Perkins. This letter, as well as several other pieces of correspondence between Perkins, the Kellers, and Sullivan, is available via the Digital Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Anagnos wrote:

“Please read the enclosed letters carefully, and let me know at your earliest convenience whether you would be disposed to consider favorably an offer of a position in the family of Mr. Keller as governess of his little deaf-mute and blind daughter. I have no other information about the standing and responsibility of the man save that contained in his own letters: but, if you decide to be a candidate for the position, it is an easy matter to write and ask for further particulars.”

Did Helen Keller Win a Nobel Prize?

It’s the viral story’s ending, however, that conflicts the most with reality. In the viral version, Keller receives the Nobel Prize, thanks Sullivan, and is then reminded that neither of them would have been successful if it weren’t for the kindness of a maid. There are two problems with this ending. First, Sullivan died in 1936, more than 15 years before Keller was first nominated for the prize in 1954. And second, while Keller was nominated multiple times, she was never actually awarded the prize.

While this viral story does mirror some true events from the lives of Keller and Sullivan, it fudges a few details, invents quotations, and incorrectly states that Keller won a Nobel Prize. This story would be more accurately described as an inspirational parable loosely based on a true story, not a historically accurate account of the lives of Keller, her teacher, and the random act of kindness that changed their lives.

Sources:

“Anne Sullivan.” Perkins School for the Blind, 25 Sept. 2014, https://www.perkins.org/anne-sullivan/.

Article from the New York Times about Nella Braddy’s New Biography of Anne Sullivan Macy.“People Make the Place.” Nursing Management Magazine.

https://journals.lww.com/nursingmanagement/Citation/1993/05000/People_Make_the_Place.1.aspx. Accessed 5 Oct. 2021.“Death of Anne Sullivan Macy.” The American Foundation for the Blind, https://www.afb.org/about-afb/history/online-museums/anne-sullivan-miracle-worker/final-years-and-legacy/death-anne. Accessed 5 Oct. 2021.

Letter from Michael Anagnos to Annie Sullivan, August 26, 1886. https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:b8516440c. Accessed 5 Oct. 2021.

Manuscript by Anne Sullivan Macy Entitled “Foolish Remarks of a Foolish Woman”. https://www.afb.org/HelenKellerArchive?a=d&d=A-HK01-03-B071-F11-009.1.13&e=——-en-20–1–txt——–3——————0-1. Accessed 5 Oct. 2021.

Menand, Louis. “Laura’s World.” The New Yorker, June 2001. www.newyorker.com, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2001/07/02/lauras-world.

NELLA BRADDY. ANNE SULLIVAN MACY THE STORY BEHIND HELEN KELLER. DOUBLEDAY,DORAN & COMPANY,INC, 1933. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/annesullivanmacy000333mbp.

“Tewksbury Almshouse.” The American Foundation for the Blind, https://www.afb.org/about-afb/history/online-museums/anne-sullivan-miracle-worker/formative-years/tewksbury-almshouse. Accessed 5 Oct. 2021.